Case of the Week #643

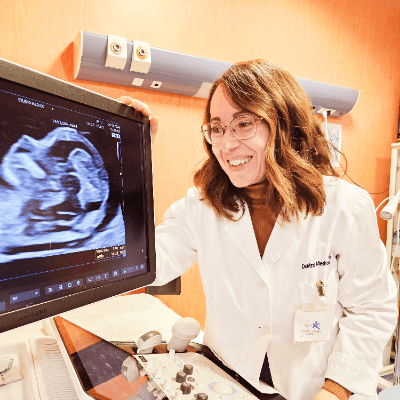

(1) Monash Ultrasound for Women; (2) Centro Médico Recoletas, Valladolid, Spain

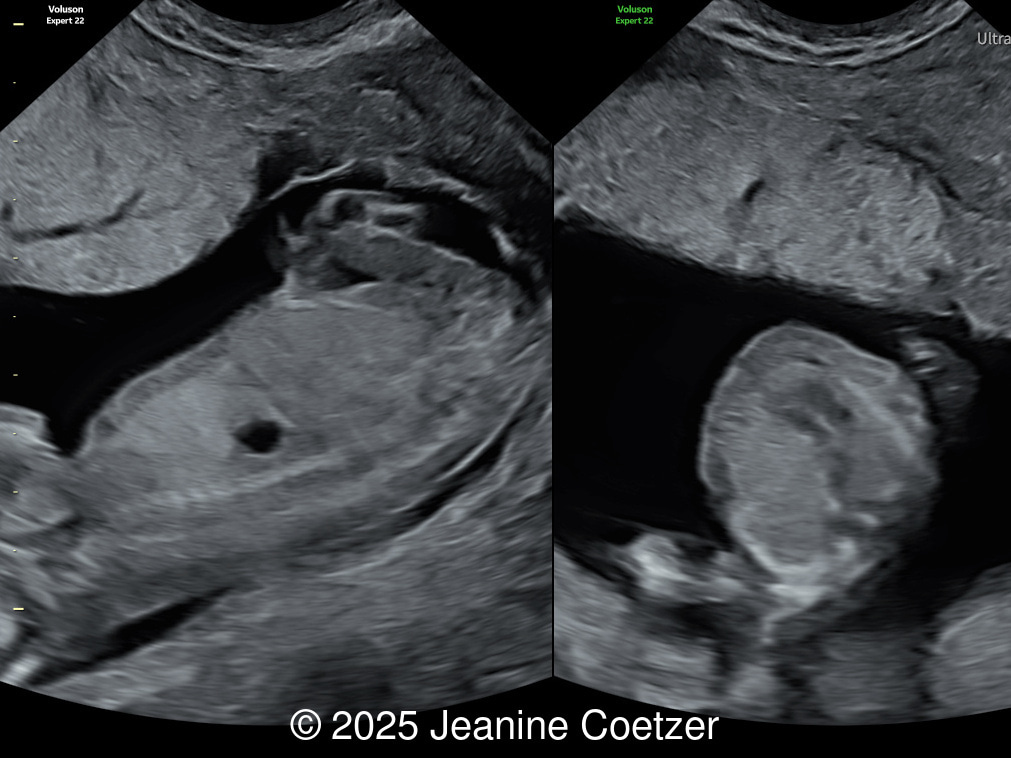

38-year-old woman with no significant previous medical history presented for her first scan at 13 weeks. This was her first pregnancy and was conceived through in vitro fertilization abroad.

View the Answer Hide the Answer

Answer

We present a case of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia diagnosed in the first trimester.

Our imaging revealed a left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia with the stomach located in the left hemithorax causing significant mediastinal shift, and right cardiac axis deviation. The four cardiac chambers and outflow tracts appeared normal. Invasive genetic testing was declined. The parents were committed to the pregnancy and did not return for follow up.

Discussion

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia is a severe malformation characterized by a defect in the diaphragm through which the abdominal viscera migrate into the fetal thorax [1,2]. The most widely used classification system is based on anatomical location [2,3]. Approximately 90% of all congenital diaphragmatic hernias are classified as being posterolateral (Bochdalek type), with 85% occurring on the left side, 13% on the right, and 2% are bilateral. Defects in the most anterior portion of the diaphragm are rare. Morgagni hernias make up 9% of total and are usually accompanied by a hernia sac. Other anterior hernias accompany Cantrell's pentalogy, and central hernias primarily involve the central tendinous portion of the diaphragm.

According to a meta-analysis including nearly 8 million live and stillbirths, the average prevalence of congenital diaphragmatic hernia is 1 in 4080 births [4]. Most cases (60%) are isolated, without other anatomic or chromosomal defects, however 40% are complex and present with associated anomalies [5]. More than 50 different genetic causes are associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia [6], including aneuploidies (trisomies 13, 18 and 21), chromosome copy number variants (tetrasomy 12p, Pallister-Killian syndrome), single gene mutations (Simpson-Golabi-Behmel, Cornelia de Lange, Donnai-Barrow syndrome), and syndromes with unknown genetic etiologies (Fryns syndrome). It has been postulated that the embryogenesis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia is due to a failure of fusion of the pleuroperitoneal folds with the septum transversum, the esophageal mesentery, and lateral body walls during the 8th week of gestation. Abdominal organs migrate into the thorax, compressing the ipsilateral lung, leading to pulmonary hypoplasia and abnormal development of pulmonary vascularization. However, there is growing evidence that ipsilateral lung abnormalities are not simply caused by intrathoracic herniation of the abdominal organs. The dual‑hit hypothesis proposes that impairment of both lungs occurs before the failed diaphragmatic closure and mechanical compression [7].

Most congenital diaphragmatic hernias are first suspected at screening ultrasounds between the 18th to 22nd weeks of gestation, however they have been identified as early as the first trimester of pregnancy. Approximately 50% of congenital diaphragmatic hernias are identified on the first trimester ultrasound [8]. Paladini and Volpe [9] consider diaphragmatic hernia an “evolving” lesion; Although the defect occurs in early stages of gestation, the moment at which the viscera herniate is extremely variable and ranges from the late first trimester to the first hours of life. For this reason, some cases are not detectable in the first trimester [10]. Fetal morphological assessment is usually performed in the context of combined screening for chromosomal abnormalities. Nuchal translucency is increased in almost 40% of fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia [8] and may be the consequence of venous congestion in the head and neck due to mediastinal compression and poor venous return [11]. The diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia in the first trimester has been identified in fetuses with normal [12,13] and increased [10,11,14-19] nuchal translucency. In most cases, the diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia is indirect after detecting the displacement of the heart and mediastinum caused by the abnormal intrathoracic position of the stomach and/or other viscera migrated from the abdomen; however, these signs may not be so evident in the first trimester [12,13,16,18-20]. Sagittal and parasagittal views can visualize the absence of the hypoechoic contour of the diaphragm, a tortuous path of the inferior vena cava and a cephalad course of the superior mesenteric artery [9,21]. Abuhamad and Chaoui [20] consider that the key findings for the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia in the first trimester are a more cranial position of the stomach in the coronal view of the thorax and abdomen, the slight change of cardiac position in the four-chamber view, and the abnormal course of the ductus venosus in the abdomen.

The most important prognostic factor for fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia is the association with chromosomal abnormalities or genetic syndromes. An invasive test (usually amniocentesis) is mandatory for genetic testing, which should include karyotyping, CGH array, and, if possible, whole-exome sequencing. For isolated cases, the most accepted prognostic parameters in the second and third trimesters are the assessment of the amount of the lung tissue (evaluated by the observed/expected lung-to-head ratio -o/e LHR-) and the presence of liver herniation. This can be difficult to assess in the first trimester. Therefore, the association of congenital diaphragmatic hernia with increased nuchal translucency and even the fact of early diagnosis itself could be more predictive of outcome in the first trimester. The association of increased nuchal translucency and congenital diaphragmatic hernia suggests a poor outcome, even after ruling out chromosomal or genetic defects [17]. The neonatal mortality rate decreases significantly with increasing gestational age at diagnosis, with rates of approximately 60%, 40%, and 10% in the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively, with similar results for respiratory morbidity (persistent pulmonary hypertension) [22].

The differential diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia includes any intrathoracic lesion that displaces the fetal heart or lungs, including cystic (congenital pulmonary airway malformation, bronchogenic cyst) and solid lesions (bronchopulmonary sequestration, bronchial atresia, and mediastinal teratoma) [1,23,24]. In these cases, the intra-abdominal organs do not shift into the thorax, and characteristic findings can be found: multiple cystic lesions in congenital malformations of the pulmonary airways and a systemic feeding vessel in bronchopulmonary sequestration.

The recurrence risk for apparently isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia is approximately 1-2%. While this recurrence risk is low, the recurrence risk increases 20-fold compared to the incidence of this pathology in the general population. Therefore, subsequent pregnancies should be monitored with fetal imaging [5].

References

- Russo FM, van der Merwe J, Aertsen M, Devlieger R, Lewi L, De Catte L, and Deprest J. Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. In: Copel JA, ed. Obstetric Imaging. Fetal diagnosis and care, 3rd ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2026; pag 320- 326.e1.

- Chandrasekharan PK, Rawat M, Madappa R, et al. Congenital Diaphragmatic hernia - a review. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017 Mar 11;3:6.

- Pober BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects, and chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007 May 15;145C(2):158-171.

- Skari H, Bjornland K, Haugen G, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a meta-analysis of mortality factors. J Pediatr Surg. 2000 Aug;35(8):1187-1197.

- Pober BR. Genetic aspects of human congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Clin Genet. 2008 Jul;74(1):1-15.

- Wynn J, Yu L, Chung WK. Genetic causes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014 Dec;19(6):324-330.

- Keijzer R, Liu J, Deimling J, et al. Dual-hit hypothesis explains pulmonary hypoplasia in the nitrofen model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Pathol. 2000 Apr;156(4):1299-1306.

- Syngelaki A, Chelemen T, Dagklis T, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of fetal non-chromosomal abnormalities at 11-13 weeks. Prenat Diagn. 2011 Jan;31(1):90-102.

- Paladini D and Volpe P. Thoracic Anomalies. In: Ultrasound of congenital fetal anomalies: differential diagnosis and prognostic indicators, 3rd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2024; pag 419-457.

- Sepulveda W, Wong AE, Casasbuenas A, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in a first-trimester ultrasound aneuploidy screening program. Prenat Diagn. 2008 Jun;28(6):531-534.

- Sebire NJ, Snijders RJ, Davenport M, et al. Fetal nuchal translucency thickness at 10-14 weeks' gestation and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Dec;90(6):943-946.

- Daskalakis G, Anastasakis E, Souka A, et al. First trimester ultrasound diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007 Dec;33(6):870-872.

- Sousa Ferreira B, Martins M, Correia A, Moutinho O. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a rare first trimester prenatal diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2025 Feb 24;18(2):e263713.

- Lam YH, Tang MH, Yuen ST. Ultrasound diagnosis of fetal diaphragmatic hernia and complex congenital heart disease at 12 weeks' gestation--a case report. Prenat Diagn. 1998 Nov;18(11):1159-1162.

- Lam YH, Eik-Nes SH, Tang MH, et al. Prenatal sonographic features of spondylocostal dysostosis and diaphragmatic hernia in the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Mar;13(3):213-215.

- Varlet F, Bousquet F, Clemenson A, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Two cases with early prenatal diagnosis and increased nuchal translucency. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2003 Jan-Feb;18(1):33-35.

- Spaggiari E, Stirnemann J, Ville Y. Outcome in fetuses with isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia with increased nuchal translucency thickness in first trimester. Prenat Diagn. 2012 Mar;32(3):268-271.

- Jensen KK, Sohaey R. First-Trimester Diagnosis of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Ultrasound Q. 2016 Dec;32(4):370-372.

- Di Gregorio DM, Martin D, Mansilla L. First Trimester Cystic Hygroma: Herald to Early Diagnosis of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. P R Health Sci J. 2021 Mar;40(1):53-55.

- Abuhamad A, Chaoui R. The Fetal Chest. In: First trimester ultrasound diagnosis of fetal abnormalities, 1st ed. Wolters Kluwer Heath, Philadelphia, PE, 2018; pag 179-190.

- Lakshmy RS, Agnees J, Rose N. The Upturned Superior Mesenteric Artery Sign for First-Trimester Detection of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and Omphalocele. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 Mar;36(3):583-592.

- Bouchghoul H, Senat MV, Storme L, et al; Center for Rare Diseases for Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: does gestational age at diagnosis matter when evaluating morbidity and mortality? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct;213(4):535.e1-7.

- Claus F, Sandaite I, DeKoninck P, et al. Prenatal anatomical imaging in fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;29(1):88-100.

- Kosiński P, Wielgoś M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: pathogenesis, prenatal diagnosis and management - literature review. Ginekol Pol. 2017;88(1):24-30.

Discussion Board

Winners

Azar Farajov Azerbaijan Physician

Zhanna Bondarchuk Ukraine Physician

Emad Abdelrahim Elshorbagy Egypt Physician

Dianna Heidinger United States Sonographer

paola quaresima Italy Physician

Padman KG United Kingdom Sonographer

Pawel Swietlicki Poland Physician

Andrii Averianov Ukraine Physician

Alexandr Krasnov Ukraine Physician

Mayank Chowdhury India Physician

Nutan Thakur India Physician

Oskar Sylwestrzak Poland Physician

Vladimir Lemaire United States Physician

Shilpen Gondalia India Physician

Ivan Ivanov Russian Federation Physician

Boujemaa Oueslati Tunisia Physician

Tatiana Koipish Belarus Physician

CHARLES SARGOUNAME India Physician

Emiliano Ciari Argentina Physician

Bahauddin Sallout Saudi Arabia Physician

Kimberly Delaney United States Sonographer

Marianovella Narcisi Italy Physician

SUNIL SHAH India Physician

Yuliya Taustukha Belarus Physician

CHEN YANG China Physician

Amparo Gimeno Spain Physician

Elena Andreeva Russian Federation Physician

Muradiye YILDIRIM Turkey Physician

ALBANA CEREKJA Italy Physician

Irina Kuchma United States Sonographer

Eti Zetounie Israel Sonographer

SAMUEL GELVEZ TELLEZ Colombia Physician

Murat Cagan Turkey Physician

Mária Brešťanská Slovakia Physician

Mesud Sehic Bosnia and Herzegovina Physician

Gayane Begjanyan Armenia Physician

Ionut Valcea Romania Physician

Almaz Kinzyabulatov Russian Federation Physician

Kareem Haloub Australia Physician

Zuzana Briešková Slovakia Physician

Dr Monika Sharma India Physician

Ann-Christin Dr. Sönnichsen Germany Physician

Fred Pop Uganda Sonographer

Annette Reuss Germany Physician

Seadet Zeynalova Azerbaijan Physician

shruti Agarwal India Physician

Vu The Anh Viet Nam Physician

CHERYL TURNER United States Sonographer

YULIA VISHNEVSKAYA Russian Federation Physician

Navya KC India Physician

Lynn Davis United States Sonographer

Ismail Guzelmansur Turkey Physician

Sruthi Pydi India Physician

Laura Wharton United Kingdom Physician

philip pattyn Belgium Physician

Denys Saitarly Israel Physician

Le Tien Dung Viet Nam Physician

Tetiana Ishchenko Ukraine Physician

Costin Radu Lucian Romania Physician

Molly Brown United States Sonographer

Elizabeth Smith United States Sonographer

Philippe Viossat Antarctica Consultant

Hana Habanova Slovakia Physician

Kelsey O'Brien United States Sonographer

Marius Bogdan Muresan Romania Physician

Gnanasekar Periyasamy India Physician

Caroline Gregoir Belgium Physician

Jagdish Suthar India Physician

Valerie Finkelstein United States Sonographer

Ana Gaspar Portugal Physician

ASHLEA HARDIN United States Sonographer

Gabriel Bogdan France Physician

Kurmanzhan Balmukhambetova Kazakhstan Physician

Ali Ozgur Ersoy Turkey Physician

Manuel Rodriguez Mexico Physician

Viktorya Mkrtchyan Armenia Physician

ZHANNA Kurmangaliyeva Kazakhstan Physician

Dubyanskaya Yuliya Russian Federation Physician

Albert Guarque Rus Spain Physician

KIM SOCHETRA Cambodia Physician

Toản Dương Viet Nam Physician

Kristina Gonosova Slovakia Sonographer

jimena salcedo Spain Physician

Carmie Cee Australia Physician

Fidan Gojayev’s Azerbaijan Physician

ANDRES ARENCIBIA MOLINA United States Physician

Maria Bulanova Russian Federation Physician

Gustavo Costa Henrique Brazil Physician

Simen Vergote Canada Physician

Mert Eyupoglu Turkey Physician

Gulten Rafibeyli Azerbaijan Physician

Ayten Sadigova Azerbaijan Physician

Hessa AlSuwaidi Canada Physician

Aynur Garibova Azerbaijan Physician

Ulviyya Jafarova Azerbaijan Physician

Aida Nadirova Azerbaijan Physician

Ulviya Baylarova Azerbaijan Physician

Narmin Agabeyova Azerbaijan Physician

Mikael Huhtala Finland Physician

Almaz Huseynova Azerbaijan Physician

Nataliia Antonenko Ukraine Physician

Basma Alsayegh Bahrain Physician

mustafa kurt Turkey Physician

melike harmancı Turkey Physician