Case of the Week #621

{1) Department of Genetics, Polish Mother's Memorial Hospital, Lodz, Poland; (2) UCSF Health, San Francisco, California, USA

A woman with no significant medical history presented at 12 weeks gestation. The patient initially had a calculated risk of 1/470 for Down syndrome, though later the noninvasive prenatal testing results were normal. The rest of scan, including limbs, was normal.

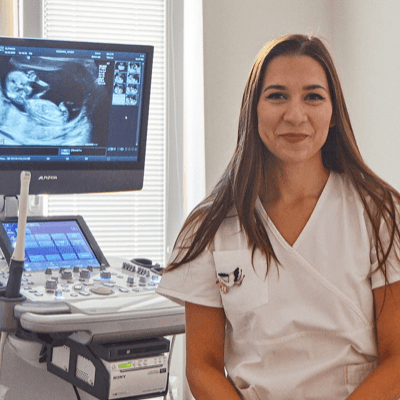

At 21 weeks during a follow-up examination, the following images were obtained.

View the Answer Hide the Answer

Answer

We present a case of isolated coronal craniosynostosis. The fetus was found to have likely isolated bicoronal synostosis, leading to characteristic cranial deformities such as brachycephaly and a tower-shaped skull. The diagnosis was confirmed postnatally. The mother declined the prenatal Whole Exome Sequencing (WES), though postnatally, the child is undergoing genetic consultation likely targeted genetic analyses, such as FGFR2 and FGFR3 gene sequencing, TWIST, or a genetic panel specific to craniosynostoses. The plan is to proceed with surgical correction.

Ultrasound findings at 12 weeks overall appeared normal, although the forehead seemed slightly more prominent. There was no obvious distortion of calvaria. At 21 weeks, an isolated (likely) bicoronal synostosis was observed with marked widened frontal and sagittal sutures, turricephaly, and a closed coronal suture. There was a normal tympanic cavity which may be hypoplastic in syndromic craniosynostoses.

Discussion

Although clinically, coronal synostosis may appear nonsyndromic, it has a genetic basis in approximately 20-30% of cases [1,2], most commonly associated with mutations in genes such as FGFR2, FGFR3, TWIST1, and others [1-3]. Genetic syndromes associated with craniosynostosis include Crouzon, Apert, Pfeiffer, and Saethre-Chotzen [3,4]. In a study reviewing 26 patients with apparently nonsyndromic coronal craniosynostosis, 31% had a mutation in FGFR3 [1], therefore, isolated synostosis should always be considered in the context of a potential genetic etiology. In nonsyndromic craniosynostosis with no confirmed genetic mutation in the affected child, the incidence of coronal craniosynostosis in a first degree relative is 0.7% [5], reflecting a potential multifactorial etiology [6]. However, if a specific mutation is identified, the recurrence risk depends on the inheritance mechanism, such as autosomal dominant inheritance which can be up to 50% risk [1,7]. Given the high genetic variability, a critical component of diagnostics involves a thorough phenotypic assessment and appropriate genetic testing to determine the underlying cause and provide an accurate recurrence risk estimate for future offspring.

Prenatal diagnosis of craniosynostosis relies on the abnormal contour of the calvarium and loss of hypoechogenicity of the synostotic sutures [4]. Indirect signs may include cranial shape, facial morphology, or abnormal cephalic index with alterations in the ratio between the biparietal diameter and occipitofrontal diameter [4,8]. Isolated craniosynostosis is only detected sporadically on fetal ultrasound and usually in the third trimester, though can be diagnosed as early as 21 weeks [4,8]. The “brain shadowing” sign has been described as an indirect sign of craniosynostosis in the absence of an abnormal skull, and is thought to be due to the premature fusion of the cranial sutures [4]. Prenatal diagnosis of syndromic craniosynostosis can be assisted by the presence of associated anomalies including limb defects (syndactyly, broad great toes or thumbs, clinodactyly), facial anomalies (midfacial hypoplasia, hypertelorism), cardiac anomalies, and polyhydramnios [1,3].

Early diagnosis allows for treatment to be initiated in the early months of life when cranial plasticity is greatest. The classic surgical approach, fronto-orbital advancement, involves decompression of the skull to allow for unrestricted brain growth, reconstruction of sutures, and improvement of cranial aesthetics and symmetry. Endoscopic suturectomy is a revolutionary approach, offering reduced surgical trauma, faster recovery, comparable aesthetic outcomes, and decreased incidence of postoperative strabismus. However, optimal results of endoscopic suturectomy are achieved in infants younger than 5 months of age, necessitating prompt diagnosis and referral for surgery [9].

Patients with coronal craniosynostosis have been found to have significantly more vision problems than those with other forms of crainosynostosis [5], which may affect neurocognitive development due to impaired visual–perceptual skills [10]. In patients with unilateral coronal craniosynostosis, the restriction in frontal brain growth associated with left-sided involvement has been associated with language-based learning disorders and developmental reading disorders, while those with right-sided involvement may have increased nonverbal learning disorders, such as social perception and functioning [10]. In a study that reviewed adolescents that had undergone surgery for craniosynostosis at less than a year of age, 30% of children with anterior plagiocephaly presented with processing and planning speech deficits, and with verbal fluency and working memory functions below average. However, almost half of patients had average or above average total IQ [11]. The group also found that 27% of patients presented with a delay in phonological expression and dyslalia in the first years of life that required speech therapy before attending primary school [11]. Given the complex nature of the disease process, multidisciplinary care is often necessary for these patients, especially when craniosynostosis has a genetic basis, and can include geneticists, neurosurgeons, orthodontists, and speech therapists.

References

[1] Moloney DM, Wall SA, Ashworth GJ, et al. Prevalence of Pro250Arg mutation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 in coronal craniosynostosis. Lancet. 1997 Apr 12;349(9058):1059-62.

[2] Wilkie AOM, Byren JC, Hurst JA, et al. Prevalence and complications of single-gene and chromosomal disorders in craniosynostosis. Pediatrics. 2010 Aug;126(2):e391-400.

[3] Gebb J, Demasio K, Dar P. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of familial Saethre-Chotzen síndrome. J Ultrasound Med. 2011 Mar;30(3):420-2.

[4] Dall'Asta A, Paramasivam G, Lees C, et al. The Brain Shadowing Sign: A Clue Finding for Early Suspicion of Craniosynostosis? Fetal Diagn Ther. 2019;45(5):357-360.

[5] Greenwood J, Flodman P, Osann K, et al. Familial incidence and associated symptoms in a population of individuals with nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Genet Med. 2014 Apr;16(4):302-10.

[6] Sanchez-Lara PA, Carmichael SL, Graham JM, et al. Fetal constraint as a potential risk factor for craniosynostosis. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 Feb;152A(2):394-400.

[7] Lajeunie E, Merrer ML, Bonaïti-Pellie C, et al. Genetic study of nonsyndromic coronal craniosynostosis. Am J Med Genet. 1995 Feb 13;55(4):500-4.

[8] Miller C, Losken HW, Towbin R, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of craniosynostosis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002 Jan;39(1):73-80. The Brain Shadowing Sign: A Clue Finding for Early Suspicion of Craniosynostosis? Fetal Diagn Ther. 2019;45(5):357-360.

[9] Isaac KV, MacKinnon S, Dagi LR, et al. Nonsyndromic Unilateral Coronal Synostosis: A Comparison of Fronto-Orbital Advancement and Endoscopic Suturectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Mar;143(3):838-848.

[10] Di Rocco C, Paternoster G, Caldarelli C, et al. Anterior plagiocephaly: epidemiology, clinical findings, diagnosis, and classification. A review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012 Sep;28(9):1413-22.

[11] Chieffo D, Tamburrini G, Massimi L, et al. Long-term neuropsychological development in single-suture craniosynostosis treated early. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010 Mar;5(3):232-7

Discussion Board

Winners

Zhanna Bondarchuk Ukraine Physician

Dianna Heidinger United States Sonographer

Javier Cortejoso Spain Physician

Dr.Neel Vaghasia India Physician

Andrii Averianov Ukraine Physician

Alexandr Krasnov Ukraine Physician

Mayank Chowdhury India Physician

Ivan Ivanov Russian Federation Physician

Boujemaa Oueslati Tunisia Physician

Tatiana Koipish Belarus Physician

carlos lopez Venezuela Physician

PRIYA R United States Physician

Kimberly Delaney United States Sonographer

CHEN YANG China Physician

ALBANA CEREKJA Italy Physician

Ionut Valcea Romania Physician

András Weidner Hungary Physician

Anette Beverdam Netherlands Sonographer

Thomson Thomson Indonesia OB-GYN

Fred Pop Uganda Sonographer

Annette Reuss Germany Physician

Jay Vaishnav India Physician

Kedarnath Dixit India Physician

Ismail Guzelmansur Turkey Physician

Ellen Cates United States Sonographer

Manisha Kala India Physician

Eylem Eşsizoğlu Turkey Physician

Petra Barboríková Slovakia Physician

Denys Saitarly Israel Physician

Tetiana Ishchenko Ukraine Physician

Kobie Golledge Australia Sonographer

Le Duc Viet Nam Physician

Hana Habanova Slovakia Physician

Joanne Maloney United States Sonographer

Petra Tallova Slovakia Physician

Hân Đỗ Viet Nam Physician

Viktoriia Putsenko Russian Federation Physician

Rotem Malihi Israel Sonographer

Ali Ozgur Ersoy Turkey Physician

JONATAS SOARES Brazil Physician