Case of the Week #612

(1) Department of Genetics, Polish Mother's Memorial Hospital, Lodz, Poland; (2) Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande, Valladolid, Spain

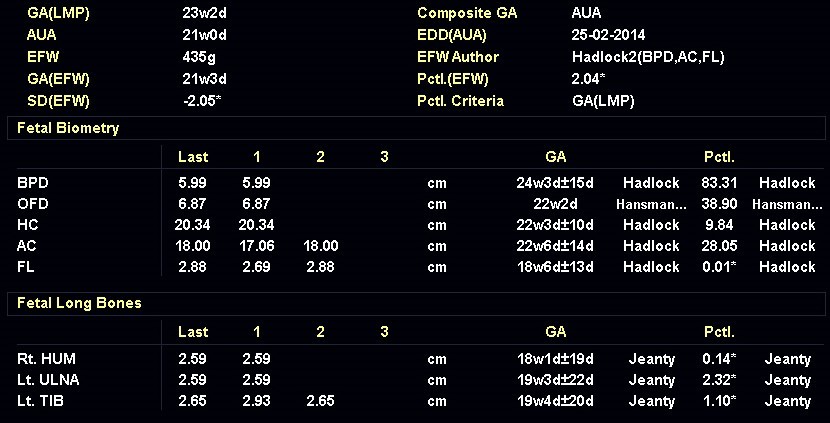

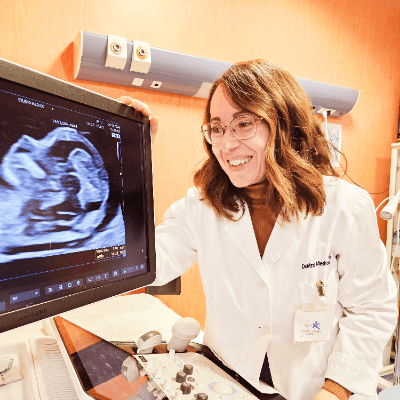

31-year-old G4P0 woman with non-contributive medical and family anamnesis was referred at 23 weeks of gestation according to a first trimester scan because of long bone shortening in the fetus. She had previous spontaneous abortions. We observed the findings shown in the following images. There were no other abnormalities noted.

View the Answer Hide the Answer

Answer

We present a case of Chondrodysplasia Punctata Phenotype due to maternal autoantibodies.

Our imaging demonstrated rhizomelic shortening of the limbs, brachydactyly, stippling of the epiphyses in the femora and humeri, and irregular stippling within the spine. The face was normal; in particular there was no midface hypoplasia, macroglossia, or echogenicity within the lenses. There was also no significant rib shortening and no abnormal ossification of the coccyx. Our preliminary diagnosis was chondrodysplasia punctata phenotype.

After the scan, the patient was questioned about the symptoms of autoimmune conditions. She recalled having high levels of ANA antibodies, identified during her work up for recurrent spontaneous abortions. Thus, our diagnosis was Chondrodysplasia Punctata Phenotype due to maternal autoantibodies.

A female neonate was born at term with a length of 46 cm (below 5th percentile), and weight of 2.95 kg (10-25 percentile). Babygram showed stippling of the epiphyses in the femora and humeri, which was consistent with Chondrodysplasia Punctata phenotype. She had rhizomelic shortening of the upper and lower limbs, and brachydactyly of both hands. No significant facial dysmorphism was noted. She had no cataracts, heart block or skin lesions that may suggest systemic lupus erythematosus. Her RBC plasmalogen levels were normal, as well as the cholesterol levels. The mother had high titers of ANA antibodies, but had no clinical signs of systemic lupus erythematosus. Chromosomal microarray (aCGH) and whole exome sequencing were performed, which failed to reveal mutations causing any known genetic syndromes in the child.

At 18 months of age, the stippling of the epiphyses detected at birth, was no longer seen. The child's height was below the 3rd percentile for age. She had rhizomelic shortening of upper and lower limbs and brachydactyly, though no other symptoms.

Recurrent spontaneous abortions may be a clue to the diagnosis of autoimmune disease, which are a known predisposing factor for fetal Chondrodysplasia Punctata. Signs of this disease are readily seen in our case, although there is no increased ossification of the coccyx, or midface hypoplasia, which are typical for more severe forms.

Discussion

Chondrodysplasia punctata is a group of skeletal dysplasias characterized by premature foci of calcification, referred to as “stippling”, within the cartilage. The areas of punctate calcification are most commonly found in the epiphysis of the long bones, vertebral column and other cartilaginous regions, such as the trachea and rib ends, that are not normally calcified [1]. The distal femoral epiphyseal ossification center is seen at 33 to 34 weeks in most fetuses, though can be seen as early as 29 weeks [2]. Visualization of the proximal and distal femoral epiphyseal ossification centers at 22 to 23 weeks gestation is always abnormal [3]. Ultrasound and X-rays can visualize these foci of calcifications prenatally, in newborns, and during childhood. Postnatally, the diagnosis is easiest in the first 2 to 3 years. When the cartilage starts to calcify, these foci are no longer visible, and the diagnosis can be missed [1,4].

Conradi first described the punctate calcifications in 1914 [5], and in 1931, Hünermann termed the condition “chondrodystrophia calcificans congenita” [6]. Chondrodysplasia punctata has an incidence of approximately 1 in 100,000 live births [7] and is caused by diverse underlying etiologies including single-gene disorders, chromosomal abnormalities, drug and teratogen exposure, vitamin K deficiency, intrauterine infections and maternal autoimmune diseases [8]. Irving et al [9] classified the etiologies of chondrodysplasia punctata into four groups: inborn error of metabolism (abnormalities of peroxisomal function and cholesterol biosynthesis), disruption of vitamin K metabolism (exposure to warfarin and severe hyperemesis), chromosomal abnormalities (trisomies 21 and 18 and Turner syndrome) and a fourth group that includes maternal factors and unclassified etiologies (systemic lupus erythematosus and fetal alcohol syndrome).

Maternal connective tissue autoimmune disorders can be associated with a number of complications in the prenatal period including recurrent miscarriages, intrauterine deaths, intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity and heart block with associated hydrops fetalis [4]. In 1993, an association between maternal systemic lupus erythematosus and chondrodysplasia punctata was simultaneously described by Costa et al [10] and Curry et al [11]. Several cases of chondrodysplasia punctata have been described in children of mothers with autoimmune diseases, most often postnatally, though there are prenatal case reports [4,12]. Furness et al. described a prenatal case of chondrodysplasia punctata in 1991 that was subsequently found to have evidence of connective tissue disease [4,13]. Initially described in association with systemic lupus erythematosus, the spectrum has subsequently expanded to other autoimmune diseases such as mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), scleroderma, and Sjögren syndrome [1,4,14]. It is not clear what causes the stippled epiphyses in maternal autoimmune conditions. A proposed explanation is that maternal autoantibodies cross the placenta and affect a specific protein, or proteins not yet known, important for the normal development of the fetal cartilage [4]. The phenotypic similarity in children of mothers affected by systemic lupus erythematosus with infants that have other forms of chondrodysplasia punctata (warfarin-mediated, and patients with X-linked recessive brachytelephalangic type) suggests that the antibodies target proteins involved in the vitamin K pathway [1]. However, the very low incidence of chondrodysplasia punctata in children of mothers with autoimmune disorders suggest that some patients may have a genetic predisposition [15].

There are multiple types of chondrodysplasia punctata, some associated with rhizomelia and others not. The rhizomelic form is more severe and inherited as an autosomal recessive condition. The nonrhizomelic form, also known as Conradi–Húnermann syndrome, is generally milder and can be inherited as both as an autosomal dominant, or as an X-linked dominant or recessive condition [16]. In all forms, there is evidence of cartilaginous stippling usually in the proximal humeri and femurs, the distal portions of the femurs, and the calcaneus that can be seen prenatally. Other findings that have been seen in different forms of chondrodysplasia punctata include coronal clefts of the vertebrae, severe disorganization of the fetal spine, distal phalangeal hypoplasia, microcephaly, cataracts, ocular coloboma, cleft palate, flat nasal bridge, micrognathia, congenital heart disease, foot deformities, and polydactyly [17]. A characteristic finding in many cases of chondrodysplasia punctata is a fetal profile morphology known as the “Binder phenotype”. Also known as maxilla-nasal dysplasia or maxillo-nasal dysostosis, this phenotype combines midface hypoplasia with absence of spina nasalis leading to a characteristic facial dysmorphism [18]. Prenatally, ultrasonographic hallmarks are flat nose with flattened nasal bridge, verticalized nasal bones, and an overall flattened midface known as an arhinoid face [19].

In a patient with chondrodysplasia punctata, an autoimmune etiology is a diagnosis of exclusion made after a complete workup that may include chromosome analysis, metabolic studies, DNA analysis and, if needed, whole exome sequencing [1]. A pregnant woman with autoimmune disease or carrier of autoantibodies is often monitored for fetal heart block and bradycardia, however it is important to also evaluate the fetus for Chondrodysplasia punctata.

References:

[1] Alrukban H, Chitayat D. Fetal chondrodysplasia punctata associated with maternal autoimmune diseases: a review. Appl Clin Genet. 2018 Apr 20;11:31-44.

[2] Goldstein I, Lockwood C, Belanger K, Hobbins J. Ultrasonographic assessment of gestational age with the distal femoral and proximal tibial ossification centers in the third trimester. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Jan;158(1):127-30.

[3] Pradhan GM, Chaubal NG, Chaubal JN, et al. Second-trimester sonographic diagnosis of nonrhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata. J Ultrasound Med. 2002 Mar;21(3):345-9.

[4] Chitayat D, Keating S, Zand DJ, et al. Chondrodysplasia punctata associated with maternal autoimmune diseases: expanding the spectrum from systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) to mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) and scleroderma report of eight cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2008 Dec 1;146A(23):3038-53.

[5] Conradi E. Vorzeitiges auftreten von knochen und eigenartigen verkalkuns kernen bei chondrodystrophia fetalis hypoplastica: histologische und ront neuntersuchungen. J Kinderheilkd. 1914; 80: 86.

[6] Hünermann C. Chondrodystrophia calcificans congenita as abortive form of chondrodystrophy. Z Pediatrics 1931; 51: 1-19.

[7] Stoll C, Dott B, Roth MP, et al. Birth prevalence rates of skeletal dysplasias. Clin Genet. 1989 Feb;35(2):88-92.

[8] Poznanski AK. Punctate epiphyses: a radiological sign not a disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24(6):418-24, 436.

[9] Irving MD, Chitty LS, Mansour S, et al. Chondrodysplasia punctata: a clinical diagnostic and radiological review. Clin Dysmorphol. 2008 Oct;17(4):229-41.

[10] Costa T, Tiller G, Chitayat D, et al. 1993. Maternal systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) and chondrodysplasia punctata in two infants. Coincidence or association? 1st Meeting of International Skeletal Dysplasia Society, Chicago, June 1993.

[11] Curry CJR, Micek M, Bertken R, et al. 1993. Chondrodysplasia punctata associated with maternal collagen vascular disease. A new etiology? Presented at the David W. Smith Workshop on Morphogenesis and Malformations, Mont Tremblant, Quebec, August 1993.

[12] Elçioglu N, Hall CM. Maternal systemic lupus erythematosus and chondrodysplasia punctata in two sibs: phenocopy or coincidence? J Med Genet. 1998 Aug;35(8):690-4.

[13] Furness ME, Haan EA, Hopkins PB, et al. Chondrodysplasia punctata, mild symmetric type with echogenic coccyx in a 15-week fetus. Fetus 1991; 1: 1–3. https://thefetus.net/content/chondrodysplasia-punctata-mild-symmetric-type-with-echogenic-coccyx-in-a-15-week-fetus/

[14] Huarte NM, Santos-Simarro F, Abascal IP, et al. Chondrodysplasia punctata associated with maternal Sjögren syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2014 Jun;164A(6):1606-10.

[15] Toriello HV. Chondrodysplasia punctata and maternal systemic lupus erythematosus. J Med Genet. 1998 Aug;35(8):698-9.

[16] Bianchi DW, Crombleholme TM, D’Alton ME, et al. Chondrodysplasia Punctata. In: Fetology. Diagnosis and Management of the Fetal Patient, Second Edition. Mc Graw Hill Medical, New York, 2010; pages 677-686.

[17] Krakow D. Chondrodysplasia Punctata. In: Copel JA, ed. Obstetric Imaging. Fetal diagnosis and care, 2nd ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2018; pag 259-261.e1.

[18] Levaillant JM, Moeglin D, Zouiten K, et al. Binder phenotype: clinical and etiological heterogeneity of the so-called Binder maxillonasal dysplasia in prenatally diagnosed cases, and review of the literature. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29(2):140–150.

[19] Blask AR, Rubio EI, Chapman KA, et al. Severe nasomaxillary hypoplasia (Binder phenotype) on prenatal US/MRI: an important marker for the prenatal diagnosis of chondrodysplasia punctata. Pediatr Radiol. 2018;48(7):979–991.

Discussion Board

Winners

Dmitry Abelov Russian Federation Physician

Andrii Averianov Ukraine Physician

Ana Ferrero Spain Physician

Alexandr Krasnov Ukraine Physician

Carlos Orellana Venezuela Physician

Mayank Chowdhury India Physician

RITIKA BHANDARI India Physician

Tatiana Koipish Belarus Physician

carlos lopez Venezuela Physician

CHARLES SARGOUNAME India Physician

RANJAN DUTTA India Physician

Olivia Ionescu United Kingdom Physician

Marianovella Narcisi Italy Physician

ARAVIND NARAVULA India Physician

Tudor Iacovache Romania Physician

Muradiye YILDIRIM Turkey Physician

CRISTINA MARTINEZ PAYO Spain Physician

ALBANA CEREKJA Italy Physician

Eti Zetounie Israel Sonographer

Deval Shah India Physician

Murat Cagan Turkey Physician

gholamreza azizi Iran, Islamic Republic of Physician

Ionut Valcea Romania Physician

Đặng Mai Quỳnh Viet Nam Physician

Halil Korkut Dağlar United States Physician

Kathrine Montagne United States Sonographer

abdullah sarıyıldırım Turkey Physician

Annette Reuss Germany Physician

Vandana Yakub India Physician

Arati Appinabhavi India Physician

shruti Agarwal India Physician

shay kevorkian Israel Physician

Ismail Guzelmansur Turkey Physician

Sruthi Pydi India Physician

Rupal Sasani India Physician

Petra Barboríková Slovakia Physician

Le Tien Dung Viet Nam Physician

Tetiana Ishchenko Ukraine Physician

Le Duc Viet Nam Physician

Tamara Yarygina Russian Federation Physician

Gnanasekar Periyasamy India Physician

Jagdish Suthar India Physician

Gabrielle Bonneville Canada Physician

Sana MV India Physician

Miguel Merino El Salvador Physician