Case of the Week #574

*Yaroslavl, Russia; **United Kingdom

18-year-old primigravida with no past medical history presents with the following findings on routine first trimester screening.

View the Answer Hide the Answer

Answer

We present a case of left-sided gastroschisis.

Discussion

Gastroschisis is a congenital malformation characterised by intestinal herniation through the abdominal wall. The incidence of gastroschisis is increasing, and estimated prevalence ranges between 2.6 per 10,000 live births in Europe to 4.3 per 10,000 live births in the USA [1]. Risk factors for the development of gastroschisis include primigravidity, adolescent pregnancy, low socioeconomic status, poor diet, smoking and illicit drug use [2,3]. Isolated gastroschisis is not linked to chromosomal abnormalities, and most centres therefore do not offer routine invasive genetic testing [3]. Termination of pregnancy for isolated gastroschisis is unusual as the prognosis is good: overall survival in gastroschisis exceeds 90% but is less in complex cases [3,4].

Simple and complex gastroschisis

Gastroschisis may be classified as simple or complex. Simple gastroschisis is caused by rupture of the physiological gut hernia between 10 and 14 weeks of pregnancy (the first pathological ‘hit’). The abdominal contents, primarily the distal duodenum to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon, herniate through the rupture and do not return to the abdominal cavity [1]. At birth, the herniated bowel is covered by a thickened fibrous layer known as an ‘inflammatory peel’, but is anatomically and functionally normal. Simple gastroschisis has a perinatal mortality rate of less than 5% [5].

In approximately 20% of cases, a second pathological ‘hit’ occurs and this is postulated to account for the development of complex gastroschisis [1]. There is mechanical compression and ischaemia of the herniated bowel (due to the restrictive defect in the abdominal wall), and chemical damage to the exposed bowel by digestive compounds present in amniotic fluid [1]. This results in bowel atresia, stenosis, perforation, volvulus and necrosis. Babies with complex gastroschisis have a higher prevalence of short bowel syndrome, liver failure, necrotising enterocolitis, sepsis, and often require additional surgical intervention and prolonged hospital admission. Complex gastroschisis is associated with a higher perinatal mortality rate of up to 17%. [5].

Prenatal diagnosis and management

The prenatal detection rate of gastroschisis is as high as 100% [6]. The differential diagnosis includes omphalocele, which is associated with chromosomal abnormalities and other lethal malformations, thus additional testing should be offered. In gastroschisis, bowel herniation is paraumbilical rather than at the umbilical cord insertion (Video 2), and there is no covering membrane (Video 3) [3]. Occasionally, a ruptured omphalocele may be mistaken as gastroschisis [7].

The most important role of prenatal ultrasound is to distinguish between simple and complex gastroschisis. This allows for more accurate parental counselling, prognostication and planning of neonatal care.

Intra-abdominal bowel dilatation (IABD) is the most reliable diagnostic marker to identify complex gastroschisis [1]. The presence of IABD ≥ 10mm between 20 and 22 weeks of gestation is most predictive of complex gastroschisis [8]. Additional features which are more likely to be associated with complex gastroschisis include extra-abdominal bowel dilatation, growth restriction, derangement of amniotic fluid volume, abnormal location of the gastric bubble, bowel thickening and bowel echogenicity [7,9].

The prevalence of in utero demise in cases of gastroschisis is 4.5%. It is postulated that this occurs acutely in the third trimester and may be caused by sudden umbilical cord occlusion or intestinal vascular compression leading to cardiovascular instability and death. The acute nature of such events means they are unpredictable and unpreventable [1]. However, fetal surveillance with ultrasound should continue until delivery, as there is evidence that this may reduce the risk of in utero fetal demise [10].

Evidence does not support iatrogenic preterm or early term delivery to prevent the development of complex gastroschisis or to prevent in utero demise [11]. The literature does not promote caesarean section over vaginal delivery. However, emergency caesarean section is common due to fetal monitoring concerns during labour [7].

Postnatal Care

A number of surgical techniques to repair gastroschisis have been described in the literature. These range from primary repair with or without anaesthesia in the delivery room to using a temporary silo to cover the herniated bowel until bowel oedema resolves and spontaneous reduction of the herniation occurs. Complex gastroschisis may require several surgical interventions. The infant is sustained with total parenteral nutrition and intravenous fluid until bowel function returns [1].

In the long term, children with a history of gastroschisis are prone to chronic intestinal problems such as constipation, abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux, nutritional deficiency, adhesive bowel obstruction and need for additional surgeries [1].

Prenatal therapy

There is currently no accepted prenatal treatment for gastroschisis. Efforts to prevent the second pathological ‘hit’ causing complex gastroschisis, such as amnioexchange to remove inflammatory compounds have failed to provide benefit and may even cause harm [12].

However, it has recently been proposed that fetal surgical intervention to replace the herniated bowel and repair the abdominal wall defect may reduce the risk of complex gastroschisis. Some authors suggest that fetuses at high risk of developing complex gastroschisis (i.e. with an IABD ≥ 10mm between 20 and 22 weeks of gestation) may benefit from in utero repair [13]. It is hypothesized that this will prevent ongoing intestinal ischemia, and reduce bowel exposure to toxins in amniotic fluid. Furthermore, this may prevent the cardiovascular insult which is proposed to cause in utero demise [1]. Of course, fetal surgical interventions are associated with additional complications such as preterm prelabour rupture of membranes, preterm birth and hysterotomy scar rupture [13].

References

[1] Joyeux L, Belfort MA, De Coppi P, et al. Complex gastroschisis: a new indication for fetal surgery? Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021 September: 58: 804-812.

[2] Frolov P, Alali J, Klein MD. Clinical risk factors for gastroschisis and omphalocele in humans: a review of the literature. Pediatric Surgery International. 2010 December: 26(12): 1135-48.

[3] Haddock C and Skarsgard ED. Understanding gastroschisis and its clinical management: where are we? Expert Review in Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2018 April: 12(4): 405-415.

[4] Fleurke-Rozema H, van de Kamp K, Bakker M, et al. Prevalence, timing of diagnosis and pregnancy outcome of abdominal wall defects after the introduction of a national prenatal screening program. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2017 April: 37(4): 383-388.

[5] Bergholz R, Boettcher M, Reinshagen K, et al. Complex gastroschisis is a different entity to simple gastroschisis affecting morbidity and mortality-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2014 October: 49(10): 1527-32.

[6] Stoll C, Alembik Y, Dott B, et al. Omphalocele and gastroschisis and associated malformations. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2008 May: 146A(10): 1280-5.

[7] Betat RDS, Telles JA, Gobatto AM, et al. Ruptured omphalocele mimicking gastroschisis in a fetus with Edwards syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2014 February: 164A(2): 559-60.

[8] Lap CCMM, Pistorius LR, Mulder EJH, et al. Ultrasound markers for prediction of complex gastroschisis and adverse outcome: longitudinal prospective nationwide cohort study. Ultrasound in Obstetetrics and Gynecology. 2020 June: 55: 776-785.

[9] Sun RC, Hessami K, Krispin E, et al. Prenatal ultrasonographic markers for prediction of complex gastroschisis and adverse perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2022 July: 107(4): 371-379.

[10] Perry H, Healy C, Wellesley D, et al. Intrauterine death rate in gastroschisis following the introduction of an antenatal surveillance program: Retrospective observational study. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 2017 February: 43: 492– 497.

[11] Shamshirsaz AA, Lee TC, Hair AB, et al. Elective delivery at 34 weeks vs routine obstetric care in fetal gastroschisis: randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019 September: 55: 15-19.

[12] Luton D, Mitanchez D, Winer N, et al. A randomised controlled trial of amnioexchange for fetal gastroschisis. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019 April: 126: 1233– 1241.

[13] Sacco A, Van der Veeken L, Bagshaw E et al. Maternal complications following open and fetoscopic fetal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2019 March: 39(4): 251-268.

Discussion Board

Winners

Guest United States

Emad Abdelrahim Elshorbagy Egypt Physician

Yulia Sologub Russian Federation Physician

Javier Cortejoso Spain Physician

Pawel Swietlicki Poland Physician

Kristína Bihariová Slovakia Physician

Umber Agarwal United Kingdom Maternal Fetal Medicine

Igor Yarchuk United States Sonographer

Iuliia Iudina Russian Federation Physician

belen garrido Spain Physician

Andrii Averianov Ukraine Physician

Ana Ferrero Spain Physician

Alexandr Krasnov Ukraine Physician

Tamara Nikiforova Russian Federation Physician

Mayank Chowdhury India Physician

filiz halici öztürk Turkey Physician

Oskar Sylwestrzak Poland Physician

Ahmed Ezz United States Physician

Vladimir Lemaire United States Physician

Shilpen Gondalia India Physician

Ivan Ivanov Russian Federation Physician

Tatiana Koipish Belarus Physician

Syuzanna Babloyan Armenia Physician

Michal Michna Slovakia Physician

Aysegul Ozel Turkey Physician

Rushina Patel United States Sonographer

Anita Silber Israel Physician

RANJAN DUTTA India Physician

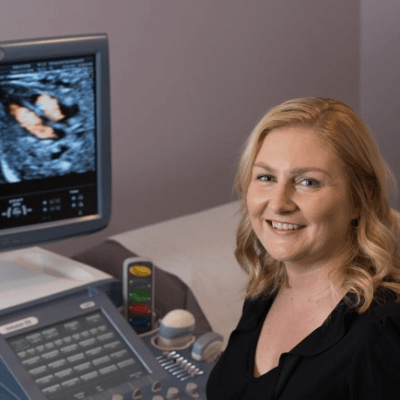

Rebecca Evans Australia Sonographer

Suat İnce Turkey Physician

Faten Badr Egypt Physician

Shari Morgan United States Sonographer

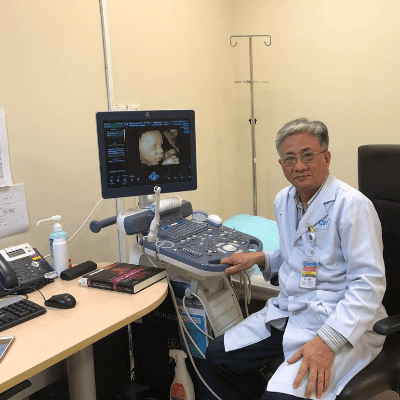

Liem Dang Le Viet Nam Physician

Amparo Gimeno Spain Physician

Elena Andreeva Russian Federation Physician

doğa öcal Turkey Physician

Murat Cagan Turkey Physician

Mesud Sehic Bosnia and Herzegovina Physician

Luiza Tsvetkova United States

Ionut Valcea Romania Physician

Jephthah Owusu-Ansah United States RDMS

Đặng Mai Quỳnh Viet Nam Physician

Prakriti Patil India Physician

KHALED RAMADAN Egypt Physician

mahmoud elbohy Egypt Physician

Seda Cam Turkey Physician

Kathrine Montagne United States Sonographer

Miguel Sanchez Mexico Physician

Almaz Kinzyabulatov Russian Federation Physician

Sumit Singhania India Radiologist

Dr Monika Sharma India Physician

Martina Vagaská Slovakia Physician

Maria Kuznetsova Russian Federation Physician

Hüseyin Sert Turkey Physician

Camilo Olivares Peñailillo Chile Sonographer

Magdalena Drąg-Drogoń Poland Physician

Arati Appinabhavi India Physician

Can Ozan Ulusoy Turkey Physician

Ildar Daminov Russian Federation Physician

Janoub Khazaal France Physician

Kadriye yakut yücel Turkey Physician

shruti Agarwal India Physician

Jayprakash Shah India Fetal Medicine expert

Mequanint Melesse Bicha Ethiopia Physician

Vu The Anh Viet Nam Physician

Jay Vaishnav India Physician

CHERYL TURNER United States Sonographer

Jerome Agbekpornu Ghana Sonographer

Lois Amoah-Kumi Ghana Sonographer

Adumatta Michael Ghana Sonographer

Prince Apau Ghana Sonographer

Ellen Maddux United States Sonographer

Natalya Puryskina Russian Federation Physician

Brindusa Ciobanu Romania Physician

Ebtihal Bin jomaa Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Physician